As I paid for my room on Thursday morning, I saw the receptionist applying the beige paste that is so popular here on her son's face, as he sat wriggling on her lap. She had a round, flat whetstone, and a section of a branch an inch or so in diameter. Having poured some bottled water onto the stone, she was grinding the branch in circular movements, then wiping the resulting liquid onto the boy's face. I believe the wood is called thanakha, and that it's just the bark that is used. It's available from chemists, ready mixed too. Some women (men too) apply it in neat geometric shapes, others in dots or spirals, and some just slap it on all over. It's one of the main things, I think, that gives this country such a "foreign" feel to it.

Outside the hotel I caught a stagecoach, feeling a bit like Alice in Wonderland as I folded myself into it. At the train station I queued up at the ticket window, waiting not-so-patiently as some people pushed in (I know it's stereotypically British of me, but I get so hot under the collar at queue-jumpers). As I berated one young lad, the man behind the window - which had been only partially slid back resulting in a slit which the uniformed man peeked through - spotted me, and bade me to come in. It seemed I needn't have queued at all; one perk for having to pay the much greater foreigner rate, I guess. I was asked whether I wanted first class or ordinary, and had a bit of a "because I'm worth it" moment, and asked for first class (I'd never do this in Thailand, where I pride myself on travelling third class whenever I can). I popped into the tea shop, where I had a tasty strip of fried dough, a bit like a doughnut that someone had forgotten to join together, and waited for the train to arrive.

I could tell it was coming, because all the hawkers burst into a sudden flurry of activity, hoisting plates of assorted goodies onto their heads, and securing a prime position along the platform. I found the first-class carriage, double-checked that it really was first class, as it didn't look like it (I think the difference was a thinly padded piece of vinyl placed on the wooden, slatted seat), and found my seat. We were in the station for around half an hour before pulling out, and I chatted to the teacher from Yangon, who was getting off at the next stop to visit a waterfall with his family. That stop was what I thought of as a non-station; it appeared to be in the middle of nowhere, no building in sight. What was there, though, were twenty or so women laden with carrots, and a few with turnips, and purchases were made through the train window.

The journey continued, past ploughed fields, and pagodas, and distant hills. We stopped at stations specialising in flowers, and passed men washing tractors in rivers. People got off along the way, passing a multitude of belongings through the open window, and a few got on. After a couple of hours I got a glimpse of an approaching gorge, and figured this was it; the highlight of the trip; my reason for catching the slow, expensive train rather than the bus: Gokteik Viaduct. I've got a bit of a bridge fetish, and have been known to drool at the Dartford river crossing, so I was very excited about this engineering marvel. The viaduct was built at the turn of the last century by the Pennsylvania Steel Company, and was - at the time - the second highest railway bridge, and considered to be the greatest viaduct in the world.

I was frustrated by being on the wrong side of the train, so moved to the front of the carriage (leaping over a lady asleep in the aisle surrounded by her bags in the process - the joys of first-class travel!), where I could get an unobstructed view from either of the open doors. There were a lot of trees in the way, and the bridge was still far away, but I took a couple of warm-up shots nonetheless. Then I was approached by a man in uniform who waved his hands at me whilst saying something unintelligible to my ears. I understood what he was saying, though I pretended not to: I could not take photographs of the bridge, which is considered to be of strategic importance. I was aware that theoretically I wasn't supposed to take pictures, but I'd believed the Lonely Planet when it told me, "the military supposedly forbids photo-taking from the bridge, but everybody seems to do it", and didn't think it would be a problem.

My heart sunk as I did my best to look like I had no clue at all to what he was saying. Too soon, though, they found a passenger who spoke some English, and got him to translate. I returned to my seat, for fear of getting the guy into trouble, muttering as I went. I waited a few minutes, then tried a surreptitious shot through the opposite window, which prompted a different man in uniform to come and speak to me. I tried arguing, asking why I couldn't, but to no avail. I was really gutted. Spectacular scenery, a fantastic bridge, a train moving slowly enough to take well framed shots, and I wasn't allowed to; it was painful. What could I do? I'd pushed my luck far enough, and had to make do with just looking as we crossed the gorge. I fumed as the uniformed man watched me like a hawk.

The scenery was too good to be angry for long, as we chugged past rolling green fields, interspersed with big old trees and the occasional far-off stupa. Not long after three o'clock (so pretty much on time) we arrived in Hsipaw, and I was met off the train by representatives from the town's three guest houses. I'd already decided to stay at Nam Khae Mao, next to a clock tower that no longer chimes (they asked for it not to be mended when it broke down, as it was too loud). Proving yet again that I am no longer a shoestring traveller, I opted to stay in an en suite room for $5. This is the first place I've stayed that I can honestly say is clean, even the sheets. The staff are wonderfully welcoming. We were discussing the fact that it is low season, so there are few customers (I'm the only fahlang in the village), when one of them mentioned that there might be more visitors to Myanmar now that people are afraid to go to Bali after the bomb. This was the first I'd heard of another bomb there (and I felt ashamed not to have checked the news when I was online in Mandalay). I watched the BBC World news later (which they have via satellite), but there was no mention of it.

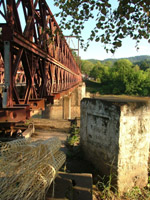

Once I'd showered, and scattered my belongings all over the room, I set off for a nearby hill to watch the sunset from. I walked out of town on the road to Lashio, crossing the sturdy-looking, iron bridge built in 1846, which wobbled worringly when one of the large lorries drove across, forcing me to squeeze up against the criss-crossed girders and hope for the best. A little further on I took a path off to the left, lined with a life-size concrete Buddha image, followed by a number of slightly smaller monks carrying alms bowls. I followed the path as it wound upwards, and after thirty minutes or so arrived at Nine Buddhas pagoda. The sounds of a transistor radio drifted down to me, and I saw that it was held by an elderly monk, with a kind face, whom I spoke to for a while.

Sunset was still an hour away, so I said I'd check out the views from nearby Five Buddha pagoda. The monk came with me, and I asked him how many monks were at his monastery. "Only one," he replied. He was 69 years old, and had been a monk for the past twenty years. I asked whether he'd had a family before going in to the monkhood. He told me he'd had five children, three daughters and two sons, but they had all died. I didn't pry further by asking how. Every morning he descends from his hill, and walks into town, living off of the food he is given by the faithful. We reached the monastery, where he told me two monks live, and I searched in vain for a clear view of the valley. When I looked back at him, he was chuckling and shaking his head "no good," he said.

"No," I agreed, "let's go back to yours."

The sun was spreading an orange glow over the clouds as it sunk behind distant hills, which changed to a deep pink in its wake. I looked behind me, and saw there was an unobstructed view to the east too, and I asked him if he got to see the sun rise too. A beautiful smile spread across his features, as he nodded enthusiastically and said, "yes!" His eyes twinkled. Twenty years alone on a hill with splendid sunsets and sunrises to keep you company; I think I could handle that. I said goodbye, and left him to his meditations, climbing down the hill before the light faded.

---------

This morning I enjoyed my breakfast of two eggs, fried, four slices of toast, two bananas, two cups of coffee, and Chinese tea. I chatted while I ate to one of the guys who works at the guest house. He told me he came from Kayin State, but had moved as it is a troubled area; his parents now live in Yangon. I asked him whether he had spent any time as a novice in his youth - it is common for men to enter the monkhood twice in Myanmar, once as a novice, when they are under twenty, and again as a monk later in life. He said that he'd been a novice twice, each time for just two weeks. I asked whether he would spend time also as a monk. "I can't, because of this," he said, gesturing downwards. I hadn't noticed, but he had a prosthetic foot. He had stepped on a landmine five years ago, and had it amputated mid-calf. "There are many like me where I come from," he told me. In Myanmar, when entering the grounds of a temple, it is necessary to remove all footwear, even socks; you can only step on the hallowed ground with your two feet. It seemed an awfully cruel twist.

I spent the day wandering around the friendly town, failing to find the popcorn factory, and observing everyday life. In the river I saw vehicles, clothes and bodies being washed, and water buffalo cooling off. I saw monks on foot, monks on trucks, monks on bikes and monks sat on the entrance to a temple. I saw corn, plums and other unidentifiable things drying in the sun. The strangest thing I saw was water disappearing from a pond in a funnel, as if it were going down a drain. It was no great mystery, as a guy on the other side of the footpath was using a sunken pipe to wash something, but still it held me captivated for minutes, watching a leaf teetering on the edge of the whirlpool. I wanted to sit on the banks of the river, but unfortunately found it to resemble a rubbish tip, with associated odours. I tried at several spots, but found the same thing each time; the man who invented plastic has a lot to answer for.

Tomorrow I am going on a long trek to several villages. I wasn't too sure about this, as I have reservations about invading the privacy of remote villages, but Mr Bean (that's what he told me) was most insistent. He reckons I won't be imposing, that they're used to seeing foreigners, and love to have their photographs taken. I shall have to see whether he is right.

Visit SerenityPhotography.co.uk, where you can buy beautiful pictures from around the world...all taken by yours truly! |